The Church and the Celtic Kingdoms

431 - 1798 AD

Photograph: Celtic cross at Glendalough, a glacial valley in County Wicklow, Ireland, renowned for an early Christian monastic settlement founded in the 6th century by St Kevin. Photo credit: Declan Geraghty | CC4.0, Wikimedia Commons. Christian faith among the Celtic Irish peoples began sometime in the 5th century. The Roman Pope Celestius I sent Palladius to minister to the Irish in 431 AD, who was followed by Patrick the next year, and flourished, producing unique Christian expressions resembling the monastery movement from Egypt and Palestine. In 1798, a republican uprising attempted to assert Irish independence from England and form a republic. This uprising was suppressed by the Kingdom of Great Britain, eventually leading to a divided Ireland.

Introduction

The selection of perspectives on church history in this section — Church and Empire — has been guided by three factors: (1) to demonstrate that Christianity has not been a “white man’s religion”; (2) the study of empire as a recurring motif in Scripture by recent biblical studies scholars; and (3) explorations of biblical Christian ethics on issues of power and polity, to understand how Christians were faithful to Christ or not. Christian relational ethics continues a Christian theological anthropology that began with reflection on the human nature of Jesus, and the human experience of biblical Israel.

This section explores the experience and activities of Christians under the Celtic regimes in Ireland.

Other Resources on the Church in the Celtic Kingdoms: How the Church Shaped the Empire

Early Irish Law (Wikipedia article). Also called Brehon law, comprised the statutes which governed everyday life in Early Medieval Ireland. The early Celts were fairly nomadic, crossing Europe and eventually expanding to the British Isles. Like ancient Israel, they were more democratic in their political life, electing chieftains to lead them in battle. Christian teachings, especially in the leadership of Patrick, expanded rights for women and others.

The British Orthodox Church, On the Trail of the Seven Coptic Monks in Ireland. The British Orthodox Church Metropolis of Glastonbury. “The Coptic Orthodox Church has long known of the historic links between the British Isles and Christian Egypt, but documentation and solid evidence is thin on the ground for these early centuries of church history. There are learned articles…” See also Archbishop Lazar Puhalo, On Cassian and the Celtic Church. Brad Jersak, May 15, 2014. Puhalo notes that John Cassian drew from Eastern Christian, Egyptian Coptic monasticism, and influenced the way Celtic Christians established monasteries, used Greek, avoided Augustinian doctrines of total depravity and double predestination.

Patrick of Ireland, Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus (late 400’s). Patrick wrote a scathing letter to the British tyrant Coroticus and his men after they raided Ireland and enslaved many people. Many newly baptized Christians were among them. Patrick demonstrates the power of Christ’s authority and teaching over slavery, and the power of the church against imperial activity.

Wikipedia, Finnian of Clonard (470 – 549) (Wikipedia article) Cites Dmitry Lapa, Venerable Finnian, Abbot of Clonard. Pravoslavie, Dec 29, 2013. “Finnian established a monastery modelled on the practices of Welsh monasteries, and based on the traditions of the Desert Fathers and the study of Scripture. The rule of Clonard was known for its strictness and asceticism.” Most significant is the connection between Egyptian Christian monasticism and Irish Christian monasticism.

The Synod of Birr (Wikipedia article). In 697, a gathering of Gaelic and Pictish leaders, promulgated the Cáin Adomnáin, or "Law of Adomnán”, also known as the Lex Innocentium or “Law of Innocents.” It is named after Adomnán of Iona, ninth Abbot of Iona after St. Columba. “It is called the "Geneva Accords" of the ancient Irish and Europe's first human rights treaty, for its protection of women and non-combatants, extending the Law of Patrick, which protected monks, to civilians.” See Cáin Adomnáin (Wikipedia article). See Winston P. Nagan, “Ideological Contributions of Celtic Freedom,” edited by Nagan, John A.C. Carter, and Robert J. Munro, Human Rights and Dynamic Humanism (Leiden: Brill, 2017), chapter 4. The Brehon laws were partially eclipsed by the Norman invasion of 1169, but underwent a resurgence from the 13th until the 17th century, over the majority of the island, and survived into Early Modern Ireland in parallel with English law. Early Irish law was often mixed with Christian influence and juristic innovation. These secular laws existed in parallel, and occasionally in conflict, with canon law throughout the early Christian period.

Irish Monastic Art and Culture (c.500 – 1200) (Art Encyclopedia) Ireland had never been colonized by Rome, and remained sheltered from the Germanic invasions. Irish culture retained its own linguistic, historical, and mythological traditions, and went through a renaissance in the fifth century, and an upsurge in Christian art in the sixth century.

Wikipedia, Saint Dymphna (Wikipedia article) A historigraphical account of an Irish woman from the 7th century, honored as the patron saint of mental illness and victims of incest, because her mentally ill father, a king, pursued her in marriage. See also New Advent, St. Dymphna. The story, even if fictional, is important because of the limits Dymphna placed on her father, the king, because of Christian faith: loyalty to Christ over loyalty to father, king, or nation; ascetic chastity over family especially when incestual.

Nora K. Chadwick, The Celts. Folio | Amazon page, 1971. Chadwick’s work is a masterpiece by a literary scholar.

Thomas Cahill, How the Irish Saved Civilization. Random House | Amazon page, 1994. Cahill gives a very readable history about Irish monks and monastic centers of learning maintaining pre-Christian Greco-Roman literature.

John Philip Newell, Listening for the Heartbeat of God: A Celtic Spirituality. Paulist Press | Amazon page, 1997. Emphasizes the ongoing goodness of God’s creation, which serves as a Christian resource for creation-care. See also John Philip Newell, Celtic Treasure: Daily Scriptures and Prayer. Eerdmans | Amazon page, Oct 2005. For a readable daily prayer guide. See also John Philip Newell’s website Earth & Soul (website).

Alan Ford and Thomas O’ Loughlin, Theologians in Conversation: Celtic Christianity: Myth and Reality. University of Nottingham, Apr 24, 2012. contributions of Celtic Christianity: creation-affirming; preservation of classical learning; the codification of Western canon law; the Western discipline of penance for sins committed after baptism

Esther de Waal, An Introduction to Celtic Spirituality. St. Paul’s Cathedral, Feb 10, 2014. De Waal gives a 60 minute lecture drawing upon Nora Chadwick; explores prayerfulness, Celtic Christian artwork

Timothy O’Donnell, Island of Salvation: The Birth of Celtic Christianity. Institute of Catholic Civilization, Feb 13, 2019. O’Donnell gives a lively 60 minute video about Celtic Christian mission into Western Europe; starts with Saint Patrick’s arrival in 432, which is perhaps overly Catholic . since Patrick was a bishop and sent by Rome. and overlooks the connection between Christian Egypt which preceded Patrick. But a very good narration of Patrick and the history of Irish-Celtic monastic Christianity. Explores private penitential confession as a distinct Irish Christian practice, as inspired by “the Eastern monastic tradition.” Mentions the high view of the Irish monastic abbot as causing some functional tension with the hierarchical clergy, especially in the 7th-8th centuries. Says the the “Continental Model” of Roman bishoprics was linked to cities, which came about because of the Viking influence/invasion.

Peter Brown, Celtic Christianity Lecture 1. Samuel Weddington, Oct 3, 2019. A lecture given Feb 16, 2003. Examines with humor the story of Patrick and his significance, as a writer the first Latin prose written from outside the Roman Empire — a third world church. Roman Britain did not like the Irish and questioned Patrick. Ireland was rural, warlike, ruled in small fiefdoms, and particularly harsh on women via slavery and concubinage. Important background to Patrick’s letter to Coroticus, who was Roman and thought of himself as superior to the “barbaric” Irish whom he enslaved.

Peter Brown, Celtic Christianity Lecture 2. Samuel Weddington, Oct 3, 2019. A lecture given Feb 23, 2003. Examines Columba, the Celtic monasteries, and the context of Irish infighting for the high kingship. Columba seemed to know about the Egyptian desert fathers, and embraced the Irish form of exile . well explained as part of Ireland’s form of family-land ties. and treated the sea as a desert. Lindisfarne in northern England was founded by Irish monks, and known as “holy island.” Prayers centered on the Book of Psalms, which led to the need to guard manuscripts, study, copy, and reproduce in a process of linguistic-cultural transmission.

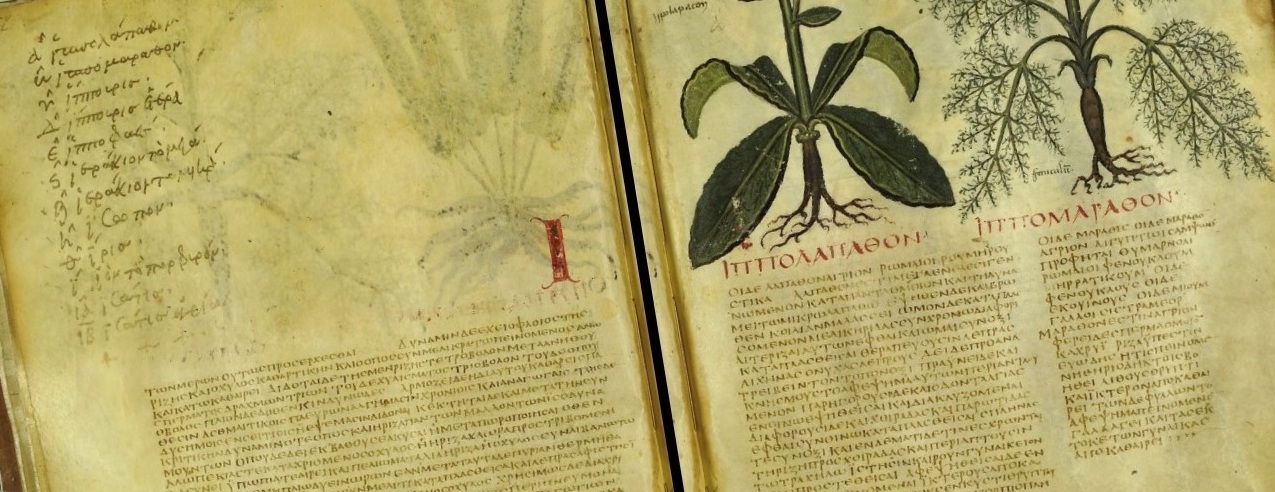

Peter Brown, Celtic Christianity Lecture 3. Samuel Weddington, Oct 3, 2019. A lecture given Mar 2, 2003. Is about Celtic Christian scholarship, poetry, and writings. Detailed description of manuscript copying of the Scriptures. Ireland had been entirely bookless prior to Christianity. Within 100 years of Patrick’s death, Irish literacy and literature emerged as the first vernacular written language using the Latin script. “Until very recently, the arrival of literacy tended to destroy the native oral culture on which it impinged. In Ireland, the exact opposite happened. Codes of Irish law, masterpieces of complex bardic poetry, and full scale epics which take us right back to the Bronze Age became fixed in writing due to the efforts of the same monks… To get an idea of what this meant, we must try to imagine an America where the epics and mythology of the Iroquois Indians had been lovingly preserved by the Pilgrim fathers, and the great royal legends of the Aztecs or the Incas published under the auspices under the Spanish Inquisition.” Irish Christians wondered about natural virtue among non-Christian peoples. Also, this led to a flourishing of literary activity in Irish societies. And, Irish Christians were fascinated by the Old Testament, seeing their own gender relations and warfare reflected.

Peter Brown, Celtic Christianity Lecture 4. Samuel Weddington, Oct 3, 2019. A lecture given Mar 9, 2003. Is about the Celtic approach to sin and penitence, starting with the Irish culture of reciprocation and gift-exchange. Prayer, not preaching, drew the Irish. The Celtic monastery was organized around holiness: monks at the center, animals and ordinary people on the outside. The Celtic monks took the spiritual practices of the Egyptian desert fathers, practiced within the monastery, and extended them to the community beyond. Christian monks gave as gift the reading of Scripture, prayers, blessings, regular confession, penance, absolution, and spiritual counsel. They practiced the practice of the “soul-friend.” Piety became available to the laity in unique ways. In the 7th century, there was no regular compulsory confession; the laity simply did it. The “Celtic penitentials” documented penances and forgiveness from the 650s/660s covered masturbation, homicide, drunkenness, etc. of teenagers, warlords, herders, etc. The system believed in happy endings. Columba gave touching marital counseling to a wife whose husband was very ugly; he asked her to pray for him, and she felt her heart changed.

French Church du Saint-Esprit, Course in Christianity - Celtic Spirituality. French Church du Saint-Esprit, Jun 30, 2020. is a magnificent 2 hour historical overview: history, theology especially about creation, missions and monasteries, stone crosses, artwork like the interwoven vines on the illuminated manuscripts and crosses, the spirituality of the labyrinth.

Elaine Breckenridge, Celebrating the Life and Legacy of St. Brigid. Godspace, Feb 1, 2022.

Church and Empire in Europe: Topics:

This section explores the experience and activities of Christians under various European regimes: the Roman Empire 313 - 800, the Celtic Kingdoms 431 - 1798, the Eastern Roman Empire 800 - 1453, the Latin Kingdoms 800 - 1787, and the Slavic Kingdoms 988 - 1917. See also our page on The Myth of Christian Ignorance, for resources contesting Christian faith as anti-science, politically backward, etc.

Church and Empire: Topics:

This page is part of our section on Church and Empire. These resources begin with a biblical exposition of Empire in Church and Empire and the meaning of Pentecost in Pentecost as Paradigm for Christianity and Cultures, then grouped by region: Middle East, Asia, Africa, Europe, Americas, then Nation-State, with special attention given to The Shoah of Nazi Germany.